We’re not 100% sure, but thinking the contrary wouldn’t make sense: Dante Alighieri, during his “last stay” in Ravenna, must have visited the splendid basilicas of the city, – today a Unesco World Heritage Site – and admired their inestimable artistic jewels.

He had already been in Ravenna before, presumably in 1303 and in 1310. He had crossed the pine forest of Classe, as he reminds in Purgatory’s canto XXVIII, where he wrote “along the shore of Classe”, describing this place as “that forest-dense, alive with green, divine”, and he must have had the chance to get to know how life was in this small town on the Adriatic.

Therefore, it mustn’t have been hard for Guido da Polenta, owner of the city, to seduce the Supreme Poet in 1318 and induce him to choose the ancient Byzantine capital as his last haven of peace and tranquility, after his long wanderings far away from his motherland Florence.

This place would have given him the opportunity to reunite his family and finish the drafting of his “beloved” Divine Comedy.

Ravenna at that time must have looked completely different from today. The splendours of the Roman and Byzantine Empire were a distant memory and the land was not hospitable at all – poor, unhealthy, and surrounded by marshes and canals.

Despite this desolated scenario, the mosaics of the ancient Byzantine churches were a shining source of light and wonder, noble, precious, and grounding witnesses of the artistic and iconological heritage of the former capital.

Their tiles and polychrome combinations are such an explosion of evocative and symbolic images that it is impossible not to be bewitched by them. And if we think to the men of those times, so poor in speech and beauty, we can understand how striking they could have been.

All the more so for such an illustrious person ― and apparently also an art expert ― as Dante, who was looking for inspiration and to find the right words to write about the Paradise and build an image of it in his mind, the mosaics meant so much to his creative work.

The basilicas and baptisteries of the ancient Byzantine capital have excellent iconographic and chromatic repertoires from which to draw: they surely provided him that immaterial sense of mysticism that helped him to design the perfect Paradise.

On the one hand the Comedy, on the other the Byzantine mosaics: such a fascinating combination pushed, during the 20th century, critics to analyse the last two parts of Dante’s work and search for triplets and images related in some way to the mosaic decorations of Ravenna.

The courts of the basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

Then I saw people following those candles,

as if behind their guides, and they wore white-whiteness

that, in this world, has never been

(Purgatory XXIX, vv. 64 – 66)

Beneath the handsome sky I have described,

twenty-four elders moved on, two by two,

and they had wreaths of lilies on their heads.

And all were singing: “You, among the daughters

of Adam, benedicta are; and may

your beauties blessed be eternally”

(Purgatory XXIX, vv. 82 – 87)

Lights, colours, golden backgrounds, and hieratic figures slowly advance in a long procession that takes Dante to the top of Purgatory. The journey culminates in Paradise, crowned by the appearance of his beloved Beatrice.

Just one glance and all those theories of virgins and martyrs that unfold in the mosaics of the majestic main nave of the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo come to mind.

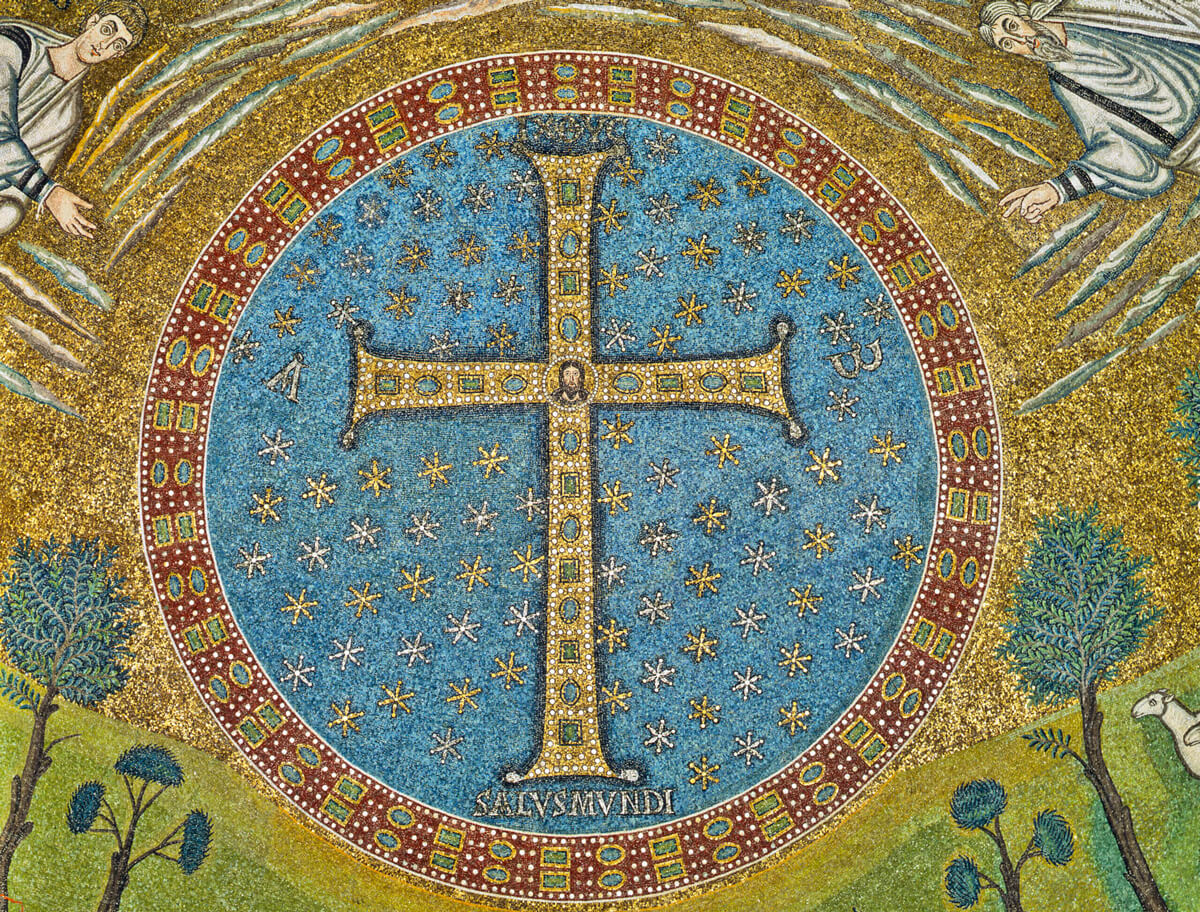

The cross of the basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe

As, graced with lesser and with larger lights

between the poles of the world, the Galaxy

gleams so that even sages are perplexed;

so, constellated in the depth

of Mars, those rays described the venerable sign

a circle’s quadrants form where they are joined.

And here my memory defeats my wit:

Christ’s flaming from that cross […]

(Paradise XIV, vv. 97 – 104)

If there is a part of the Comedy that recalls more than others the mosaics of Ravenna, it’s undoubtedly canto XIV of the Paradise.

While reading the triplets of the Supreme Poet, we find ourselves absorbed into the fifth sky, the one of Mars, enveloped in a reddish light.

Here, all the spirits who fought in the name of Faith converge, forming a Greek cross, sparkling with greater or lesser intensity, depending on their degree of bliss. And the face of Christ stands at the center.

And in this image, again, our eyes can’t be mistaken: we find, once again, a recall to the mosaic of the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe‘s apsis.

The old monument’s apsis, as a matter of fact, features a large jeweled disk decorated with a sky pierced with golden and silver stars and a jeweled cross of gems depicting Christ’s face.

San Lorenzo and the mausoleum of Galla Placidia

Had their will been as whole

as that which held Lawrence fast to the grate

(Paradise IV, vv. 82 – 83)

We are in Paradise, in the sky of the Moon, Beatrice speaks to Dante, pointing out the hero of Roman history Muzio Scevola as an example of the strength of mind and Saint Lawrence as an example of Christianity.

These descriptions immediately lead us to the image of the martyr represented in the lunette of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, still visible today as soon as you enter the monument.

We can then imagine that the Supreme Poet, who was in Ravenna when he wrote these lines, had been so fascinated by the sight of this mosaic, that he used it as a model of strength of mind.

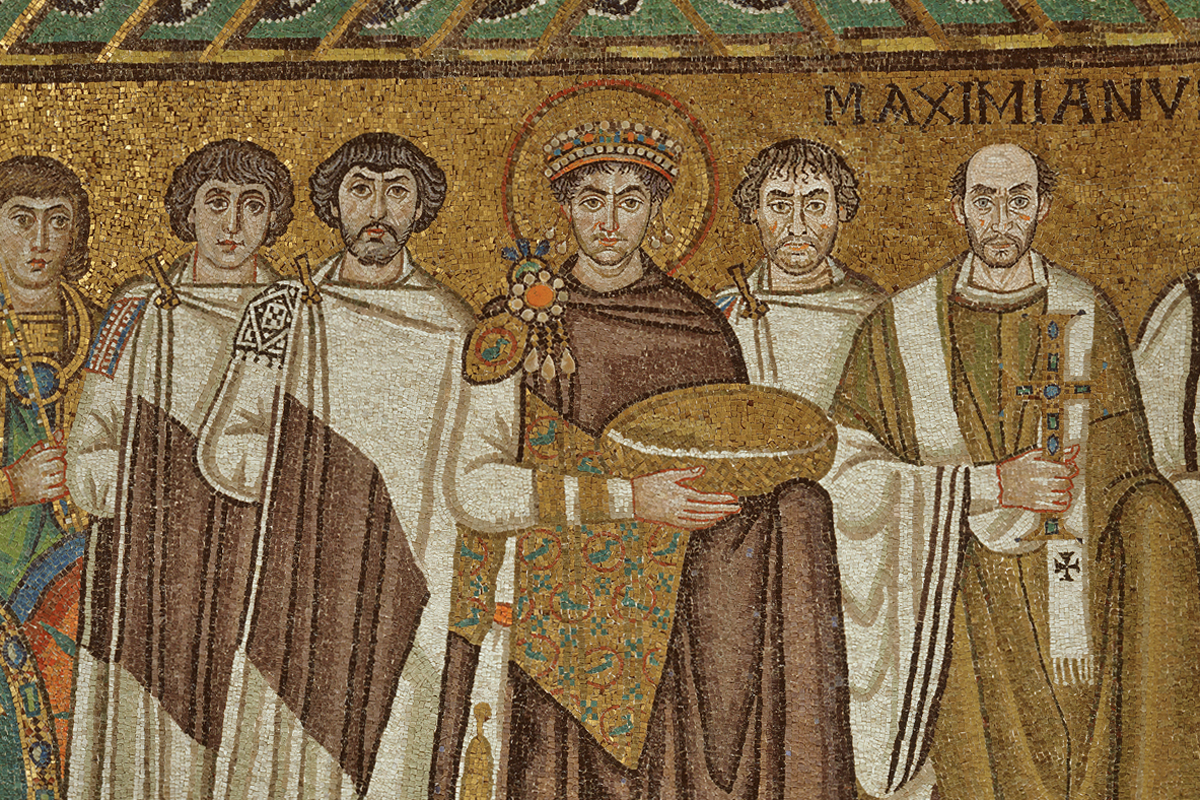

The emperor Justinian in the basilica of San Vitale

Caesar I was and am Justinian,

who, through the will of Primal Love I feel,

removed the vain and needless from the laws

(Paradise VI, vv. 10 – 12)

Faithful to that symmetry that distinguishes the other Cantiche of the Divine Comedy, even the VI canto of the Paradise deals with purely political questions. In this canto, the Supreme Poet runs into the Byzantine Emperor Justinian.

And this is an encounter that Dante had already had ― even though somewhere else. Indeed, how could we ever doubt that, during his stay in Ravenna, he had raised his eyes, and, more than once or twice, lost himself in the mosaic portrait of the emperor decorating the Basilica of San Vitale?

The virgin Mother in the basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

Virgin mother, daughter of your Son,

more humble and sublime than any creature,

fixed goal decreed from all eternity […]

(Paradise XXXIII, vv. 1 – 21)

The Great Virgin Mother, sitting on the throne at the end of the procession of the Virgins in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo.

Dante was probably inspired by this image in composing the prayer that Saint Bernard addresses to the Madonna at the beginning of the last Canto of Paradise.

A strong vision, in which the divine motherhood of Mary is exalted and which perhaps also draws on a Latin mosaic epigram that was found under the splendid image of the Madonna in Trono con Bambino in the apse of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, now gone lost.

Scholars (from Corrado Ricci to Laura Pasquini, historian and critic of Medieval Age), have connected the mosaics of Ravenna to many other fragments of the last two Canticles of the Comedy.

A universe of symbols and colours that confirm how deeply the monuments of the former Byzantine capital influenced the Supreme Poet.

Author

Davide Marino

Davide Marino was born archaeologist but ended up doing other things. Rational – but not methodic, slow – but passionate. A young enthusiast with grey hair

You may also like

Dante’s Ravenna: the most famous places of the city in 11 stages

by Davide Marino /// September 7, 2018

Interested in our newsletter?

Every first of the month, an email (in Italian) with selected contents and upcoming events.

by Davide Marino ///

by Kevin Raub ///